One editorial category particularly closely monitored, the comic genre, the descendant of illustrated stories, has been the victim of several coercive measures founded on the articles of the law of July 16, 1949, which explicitly protect the young reader.

What distinguishes the grounds of measures taken against comics from other publications is that they are motivated as much by the content as by the form: their message seems to be utterly terrifying and defies all reason.

The drawing is condemned for its violence, both the scenes described and the colours used.

Also, the ‘exaggerated’ use of onomatopoeia is regularly criticised.

Yet, in spite of these constraints, comic production in France offers a wide variety of genres, some of which were the object of bans and even self-censorship, until the appearance of ‘comics for adults’.

American comics, introduced in 1936 by Paul Winkler in Robinson, ‘the weeklies for young people of all ages’ soon attracted a French readership (who were refused their pleasure between 1942 and 1944).

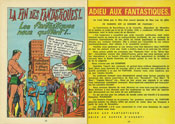

It was only after the promulgation of the 1949 law, and a few hostile campaigns led especially by the review Éducateur, that the first coercive measures were taken against these publications, such as the withdrawal of their inscription in the Société de répartition du papier, which led to the scuttling of Donald Duck (1953; 300,000 cps.) and Tarzan (1954; 200,000 cps.).

During the following years, it was essentially fantastic and sci-fi comics that came under attack by the Control committee: Mandrake (1963), Fantask (1969), Marvel (1971), in spite of the genre’s great popularity with the public.

Harking back to the practices of the forties, some publishers, especially Lug, did extensive touching up to soften the visual impact of the originals, to the great irritation of fans. This continued into the 1980s.